One of the first things we do with children is teach them the ‘names’, the ‘labels’ of things. Mummy. Daddy. Sister. Apple. Tree. Bird. We employ words to make sense of the world, to aid us in communicating with each other and to simplify the complexity we find all around us. Like a raft we use to cross a river, they are a tool we need. And, yet, too often, as soon as we know a word – say, bird – we stop seeing the fluttering musical majesty of the creature in front of us. Wielding words and told to feel proud of our learning, we stop seeing anything much at all.

Words, or labels, are shortcuts to understanding, but they are loaded with highly culturally specific meaning. Label a person daughter and, in the wider western world, as well as in the specific setting of our family and environment, we have expectations of what that person is and what that relationship should look like. But what do words such as sister, brother, cousin, aunt, lover and friend really mean?

We are all unique, and we all interact with each other and our environment in unique ways. Who is to say that an aunt can’t mean more to you than your mother? A friend more than a sister? Just because you are my son, does that mean I should expect you to care less for me than a daughter – to call less, to not look after me when I am older? And yet so much of what we tell people, about and because of those labels, restricts their connection to us. Too often, once it is labelled, we begin to take a relationship (and therefore a person) for granted. We see it, and them, through the distorted lens of our expectations and environment rather than with our own eyes.

Labels are even more restrictive when it comes to romantic relationships. We often put someone into a box labelled wife or boyfriend. The difficulty is compounded by the fact that, at least at first, the box can make the other person feel safe, secure. The danger comes when we stop seeing the person we placed inside and start to see only the box. We become attached to the box and expect it to behave in certain ways. We expect the box to stay the same, and this is when the relationship becomes a lifeless, cardboard thing. Or, as we see so often, the box is torn apart as the person inside bursts out, usually when we have forgotten there was even anything inside.

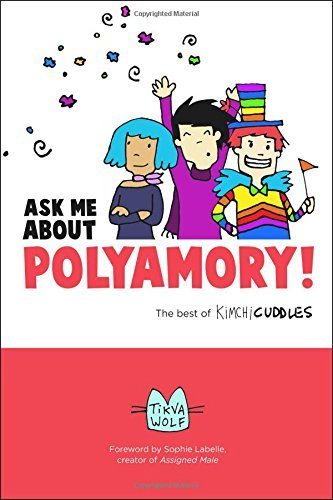

Interestingly, we accept some change in relationships (children becoming adults, friends spending less time together) but we see other change as a problem (couples no longer living together full time, couples spending time with other people).

We all, based on our past experiences and environments, have different levels of comfort when it comes to change, but, in the same way that we can develop our strength and stamina by exercise, so we can develop our comfort with change. And it doesn’t take much; all we need to do is to allow it to happen. For it is going to, whether we like it or not.

One thing that helps us to accept change is to tear off the labels. Rip them off and discard them. Doing this allows us to accept and understand that relationships are not static. Because people and relationships do change. They change and that is okay.

But what does this look like? What does letting go of labels in an environment that is obsessed with fixing things down and negating change and fluidity actually involve?

Well, it involves a degree of conscious effort in crafting your life and relationships, in shaping them and managing them, that most of us just are not used to doing. The reasons for this are embedded deep in our culture and society and are extremely complex, but they can, in essence, be reduced down to the fact that we are taught the words for people in our lives but we are not taught how to be in relationship to them: how to listen to, communicate with and understand them. And, sadly, all too often, the relationship behaviour we see modelled around is, at best, unhelpful.

What appeals about conscious relationships to an increasing number of people is the idea that who we are and how we connect with each other is for us, not society, to define, and that communication is for all the time, not just at times of crisis.

In consciously crafted relationships, people are called by their name, not by the label with which others have identified them in the past (girlfriend, brother, cousin). Simply by using a name not a label, we are reminded to see the person as they are in the now and encouraged to relate to them as they are, at this moment, not as how they were or how they are supposed to be. We don’t put them in a box. We assume nothing. Our minds are left open to the infinite possibilities of these connections, rather than being closed and shutting those possibilities out.

Once you start looking at people with an open mind, you will begin to look at life and the world in the same way. Instead of assuming people will always be there, we are grateful for their presence in our lives right now. Instead of expecting them to stay as they are, we allow and welcome changes and shifts in them and our relationship. We see them, and it, afresh every time.

This is not about never knowing where you stand; that is what trust and effective communication is for. It is about relating in this moment, about making sure that you don’t take that connection, whatever it may be, for granted. It is relational authenticity.

We need to look at and acknowledge ourselves, and others, as we, and they, truly are. Only then can we begin the work of developing relationships that are unique and wonderful, relationships that are alive.

Label-less also means limitless. And we all deserve limitless relationships; we all deserve limitless lives.